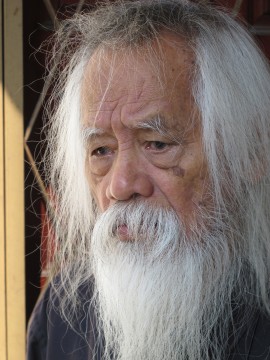

![]() Hemmed in by the towering piles of books dominating his Kuala Lumpur living room, Malaysia’s eminent poet-activist snorts with derision. “This government isn’t fair, it isn’t just,” said 77-year-old A. Samad Said. “They use racial tension.”

Hemmed in by the towering piles of books dominating his Kuala Lumpur living room, Malaysia’s eminent poet-activist snorts with derision. “This government isn’t fair, it isn’t just,” said 77-year-old A. Samad Said. “They use racial tension.”

Certainly slurs and camouflaged racial slights are flying thick and fast as the nation’s next general election creeps inexorably closer.

Special branch police, possibly acting under government orders, this week declared communists and members of the militant Jemaah Islamiah network – responsible for the Bali bombings – had tried to infiltrate Malaysia’s opposition parties. The senior special branch officer, Mohammed Makinuddin, also said opposition party leaders had been secretly meeting with communists in Thailand.

One opposition MP, Lim Kit Siang, publicly responded by saying Malaysian taxpayers should be told when special branch police had joined the ruling coalition’s propaganda arm.

Substantial minorities of Malaysia’s population are of Chinese and Indian descent. While barbed, racial attacks are usually thinly veiled with other concerns. A lawyer of Indian descent, Ambiga Sreenevasan, has become a favoured target.

With Samad Said, Sreenevasan co-chairs the democracy movement Bersih, which means “clean” in Malay. Tens of thousands of Bersih supporters rallied in April to demand electoral reform but the demonstration ended with volleys of tear gas, water cannon and prosecutions. Sreenevasan is one of ten people the government is pursuing for damage to public property during the April rally. Samad this week applied to become an intervenor in the suit on the grounds that he had been involved in organising the rally.

A national icon in Malaysia, Samad has barely been touched by the recriminations although he said he has been “scolded rudely” on the internet. But the ruling coalition MP Mohamad Aziz last month suggested Sreenevasan should be hanged for her “treasonous act”. Aziz wasn’t sanctioned for this outburst, but widespread indignation eventually forced him to apologise to the Indian community.

In yet another manifestation of racial tension, a gaggle of ex-soldiers waggled their bottoms at Sreenevasan’s house (a counter-demonstration dubbed a “backside dance” by Samad), and vendors turned up to fry meat burgers nearby, apparently intended to insult the strict vegetarian.

After some initial reluctance, Samad originally agreed to join Bersih to provide the movement with a Malay face, but it didn’t protect his co-chair from this recent flurry of spite and threats. “Ambiga is not accepted by Malays, they always attack her, saying she’s Indian and in collaboration with a group that wants to push down Malays,” he said, adding that he believed much of the impetus for the attacks comes from high in Malaysia’s ruling political echelons.

It seems Malaysia’s rulers are apprehensive about the coming poll, which has to be called before the middle of next year. The ruling coalition, Barisan National (which includes parties of Chinese and Indian Malaysians), has been in office in Malaysia for five decades in various incarnations and a burgeoning “it’s time” factor is encouraging and energising the opposition parties.

Opposition MP Liew Chin Tong, from the Democratic Action Party, said Barisan National politicians were understandably nervous because it seemed likely that if the coalition was returned, its majority would be markedly reduced. “They are worried,” said the 35-year-old ANU graduate. “They have been there too long.”

The electoral roll, he said, had increased by more than 2 million voters since the last election in 2008 when there were 10.6 million people on the roll and the government won 51 per cent of the vote. Surveys provide some frightening statistics for the government to ponder, Liew said, even though its racially skewed policies have ensured a hefty Malay vote in the past.

“Sixty per cent of Malays are aware of how UMNO (the lead party in the ruling coalition) has squandered resources,” he added. “But on current polls, the government will be returned with a slim majority. Najib (Razak, Malaysia’s prime minister) is worried about the worst case scenario.”

Ibrahim Suffian, a political analyst with the independent Merdeka Centre thinktank, said the government’s lacklustre economic performance would be a key issue in the election. Malaysians are now far better informed than ever before, with 60-65 per cent of the population using the internet. “People are getting more knowledgeable about corruption and failed promises,” Suffian said, adding Malaysians were increasingly dissatisfied with their opportunities, their income, and the ever-growing chasm between rich and poor.

For his part, Samad said only a brand new government could make the sweeping changes the nation needed. “The most important thing is regime change,” he said. “Hopefully it will change. But the road is indeed long.”