The crowded medical products aisle of the Woolworths supermarket in Sydney’s working-class suburb of Eastlakes offers a selection of nicotine products to passing consumers. Crammed on the shelf above the heartburn products is a range of quit smoking aids: nicotine gum, nicotine lozenges, nicotine patches and nicotine mouth spray.

A few metres away, at the front of the supermarket, shoppers can choose from a vast array of nicotine cigarettes — Winfield, Marlboro, Benson & Hedges — and rolling tobacco.

All these products are, of course, legal and widely available.

Nearby, in the neighbouring suburb of Beaconsfield, is The Steamery, a vaping products store where customers can buy vaporisers, starter kits, just about everything connected with electronic cigarettes and vaping.

The one thing The Steamery can’t stock is nicotine liquid, which remains illegal. E-cigarettes are legally available in Britain, the US, the EU and now New Zealand and Canada. Australia is the holdout.

E-cigarettes, battery-powered electronic devices that heat and vaporise a liquid to deliver inhalable nicotine vapour from a metal device, do not produce the tar, carbon monoxide and most of other cancer-causing chemicals of combustible cigarettes.

According to the Australian government’s QuitNow program, tar is the particulate matter generated by burning tobacco. Tar, which causes cancer, is not produced by vaping; nicotine, in both cigarettes and e-cigarettes, does not cause cancer.

Two out of three Australian smokers will die of a smoking-related illness, and it’s widely accepted that smoking cuts the average life expectancy by 10 years. The federal Health Department says smoking kills about 19,000 Australians every year.

Yet the most dangerous nicotine product, the standard issue cigarettes we all grew up with, are available everywhere, while the far less dangerous e-cigarettes that have helped wean millions of smokers away from tobacco are available in Australia only with a doctor’s prescription. E-cigarettes are also a far less expensive alternative to smoking tobacco, potentially saving thousands of dollars a year for a pack a day smoker.

Despite decades of increasing prices, hard-hitting advertising campaigns and doctors’ warnings, three million Australians continue to smoke tobacco. Most want to quit but they just can’t. They hand over often a substantial proportion of their weekly income for some of the most expensive cigarettes in the world and they endure the nagging of concerned friends and relatives.

In recent years, about 240,000 Australians have turned to e-cigarettes, despite the need to import nicotine liquid. According to many doctors, their health prospects immediately improved.

Even so, Cancer Council Australia policy director Paul Grogan says most Australian medical and public health organisations, as well as every state, territory and the commonwealth government, support a “precautionary” approach to e-cigarettes — in other words, maintaining the ban.

“That’s continuing to examine the evidence while explaining to people that there are significant risks involved going down the path of open slather for these products,” Grogan says, adding that any health damage from e-cigarettes may take decades to emerge.

“That’s continuing to examine the evidence while explaining to people that there are significant risks involved going down the path of open slather for these products,” Grogan says, adding that any health damage from e-cigarettes may take decades to emerge.

Shiny new e-cigarette products, like the many-flavoured Juuls that have become so wildly popular with US teenagers, could trigger a lifelong addiction to nicotine, he says, and the effects of inhaling chemical flavours have yet to be fully determined.

Yet there are bottom-line conclusions that can be drawn.

“The consensus is very strongly of the view that the risks (of e-cigarettes) are significantly lower (than those of smoking tobacco)” Grogan says. “And we don’t dispute that.”

A lengthy parliamentary inquiry into the use and marketing of electronic cigarettes and personal vaporisers in Australia reported in March.

Although most MPs support continuing the ban, inquiry chairman Trent Zimmerman and two of his colleagues disagreed and issued dissenting reports. Andrew Laming’s dissenting report was brief and pointed: “Life is short and shorter for smokers. Just legalise vaping.”

Liberal Democrats senator David Leyonhjelm was outraged by the inquiry’s findings. “(Federal Health Minister) Greg Hunt leant very hard on the committee to recommend against approval,” he says.

After the report was handed down, Leyonhjelm gathered support from crossbenchers and announced that until the ban on vaping was overturned, any health bills that needed crossbench support would not pass. “A couple of days after that I ran into Greg Hunt at Canberra airport, and I said, ‘This is really serious, Greg, people will die because they’re continuing to smoke when they could switch over to e-cigarettes.’ He said, ‘I think the US, the UK and Europe will regret their decision. They’ve made a big mistake.’ ”

The inquiry received more than 300 submissions, many of them from Australians championing the use of e-cigarettes. One submission came from Ron Borland, who works with the Cancer Council Victoria. Considered one of the most authoritative tobacco and smoking experts in Australia, with decades of experience in the field, Borland supports the use of e-cigarettes to help smokers quit. His submission, tellingly, was not associated with the Cancer Council.

“To make progress with the around 10 per cent of the population we have failed (those over 30 and still smoking), the only potential solution on the horizon to the remaining tobacco problem, ie one that could make a big difference, is one that has vaporised nicotine products (ie, electronic cigarettes) at its core,” he wrote in his submission.

Cancer Council Victoria declined a request for an interview with Borland. “I do know Ron and he is one of the researchers we have working on the subject,” says Grogan. “You quite often find that researchers don’t like to speak with media because they don’t want to bias their research.”

Cancer Research UK (the largest cancer charity in the world) and the American Cancer Society both endorse e-cigarettes as quit smoking aids for addicted smokers who can’t quit using other methods. Grogan says Australia has a different smoking profile and needs a different approach. “We’ve changed the culture here, more so than just about any of our colleague nations,” he says. “We’re very protective of what we do in public health here in Australia.”

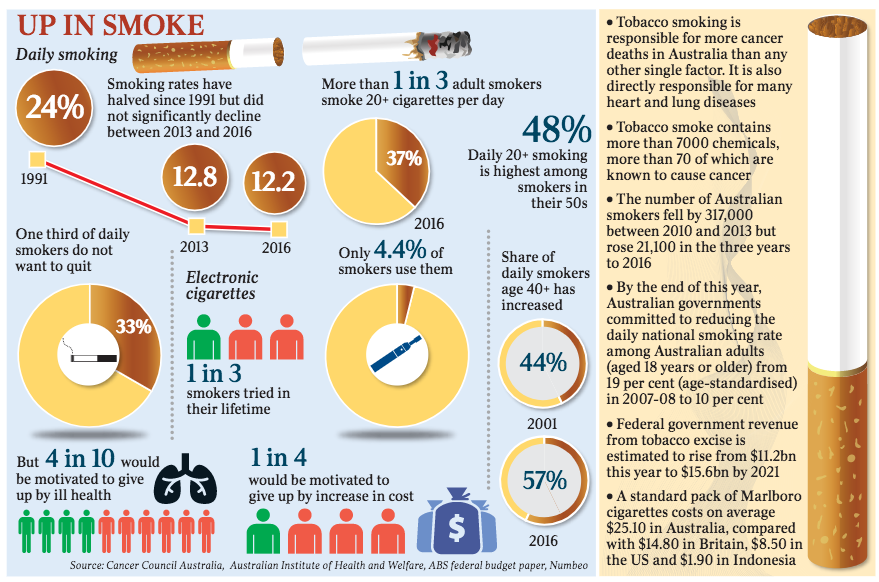

Colin Mendelsohn, a tobacco treatment expert at the University of NSW, says Australia’s smoking rate declined across many decades but has stalled during the past three to four years.

There is now a hard-core base of smokers mostly in their 40s, 50s and 60s who can’t or won’t quit. “Most of them desperately want to quit and there’s good research showing that,” Mendelsohn says.

“In the Australian National Drug Strategy household survey, about 70 per cent said they wanted to quit. They try repeatedly; they just aren’t able to.”

He disputes the idea that using e-cigarettes is a gateway to smoking tobacco. Despite hysteria about the Juul products in the US, adolescent smoking rates there are falling faster than ever, Mendelsohn says, adding that public health policy should be balanced across the entire population.

“We have no evidence to show these kids are going on to smoking,” he says. “Nicotine is relatively harmless and if (vaping) stops millions of people from smoking, you have to weigh up the benefits and risks of that.”

Mendelsohn largely agrees with US Food and Drug Administration commissioner Scott Gottlieb, who is considering restricting e-cigarettes for younger Americans, while recognising their usefulness for the “currently addicted individual adult smokers who still want to get access to satisfying levels of nicotine without many of the harmful effects that come with the combustion of tobacco”.

In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration opposes the lifting of barriers to nicotine liquid, and in 2016 refused even to assess a Big Tobacco non-electronic nicotine inhaler called Voke. British American Tobacco appealed against the decision, and a judge ruled the TGA had to assess the product and pay costs.

The shadow of Big Tobacco has darkened the e-cigarette landscape. Most e-cigarette products come from independent producers, but suspicion of the Big Tobacco companies such as Philip Morris and British American Tobacco, which do have various e-cigarette products in their portfolios, has crept across the entire market.

Tammy Chan, managing director of Philip Morris in Australia (which is committed to a “smoke-free future”), says the company has a smoke-free “heat-not-burn” product being assessed by the FDA in the US, which has an obligation to listen to the arguments and explain its decision. Conceding that any product from Big Tobacco attracts Big Suspicion, she says Philip Morris just wants the government to listen to the science.

“Three million smokers in Australia are looking for some form of alternative, with the potential to reduce harm,” she says.

“With or without a company like ours, it’s available on the market … there are a lot of electronic cigarettes available: they want this product.”

One Australian firm is working on a way to legally provide Australians with nicotine e-cigarettes, without the personal hassle of importing products.

Working within the existing regulatory environment, Nicovape plans to deliver mass-market e-cigarettes using a “precautionary” approach.

Nicovape customers will fill in an online questionnaire, which is then assessed by a registered Australian doctor who issues a prescription for nicotine. The legal vaping product then will be delivered to the customer’s home address (on a signature-required basis). A battery and three-pack of nicotine pods will cost $49.95. (Each pod is the nicotine equivalent of a packet of cigarettes, at a third the price.)

Founder Ryan Boulton says he understands the suspicion of e-cigarettes.

Yet he says the evidence is clear: e-cigarettes help addicted smokers give up tobacco. They helped him.

In 2016, he was smoking a packet of cigarettes a day, and his brother brought him a joke e-cigarette present from the US. “About two or three days after that a girl asked me for a lighter and I tapped my pocket,” he says.

“I didn’t have one. I realised I hadn’t had a cigarette for three days. I quit smoking by accident.”

https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/inquirer/its-smoking-but-not-as-weve-known-it/news-story/f4e714e1ff40a108cc6f4809a35130b5