Murders, bashings, rapes, floggings, and routine humiliation: the massive bluestone walls of Melbourne’s Pentridge prison enclosed an isolated and often barbaric world. Men were set to break rocks as punishment. Others were kept in isolation, and reacted by spreading their faeces over the prison walls – a protest known as a ‘bronze-up’. Women, imprisoned in the small and short-lived women’s section, somehow became pregnant. Mentally disturbed prisoners slashed themselves, or swallowed sharp objects, or cut off body parts. Others filled their cups with urine, or vomit, and hurled the contents at guards.

Australia’s last execution was there (Ronald Ryan in 1967); and the last flogging. From 1850 to 1997, Pentridge loomed over Melbourne, and became a byword across Australia for the horrors of jail.

The urban heritage specialist Rupert Mann was 15 or 16 when he first scaled the walls of Pentridge and began to explore inside the decommissioned prison.

Obscene graffiti that spoke of desperation and futility covered many of the walls and there was dust and filth and corrosion, but Mann, now 32, also began to see the raw and often unpalatable history of the place. When the Pentridge site was sold to developers and the destruction of many of the buildings began, he knew that he had to keep a record.

Obscene graffiti that spoke of desperation and futility covered many of the walls and there was dust and filth and corrosion, but Mann, now 32, also began to see the raw and often unpalatable history of the place. When the Pentridge site was sold to developers and the destruction of many of the buildings began, he knew that he had to keep a record.

“It was important social history, and it was being destroyed”, he says. “I couldn’t have lived with myself if I hadn’t done it”.

So he began taking a series of stark and graphic photos and, in time, tracking down people who had connection to the jail – former prisoners, a journalist, a singer, a warden. He interviewed them at length and, adding their words to the photos, he has produced a book, “Pentridge, Voices from the Other Side” that tells the story of a prison where humanity was tested and men and women treated with routine brutality. He wrote the introductions to each of the narratives, which are told in the first person.

Three of his interview subjects have since died, and Pentridge itself has been radically transformed in the years since he began the project.

“I was 23 when I started that book, and 24 or 25 when I interviewed most of these people, and that moment in my life I was really interested to ask how did you survive this place,” he says. “Then I thought if you could learn to survive Pentridge, then you could survive anything. And it’s not true, of course, because many prisoners say that learning to survive in prison is completely different to surviving in the outside world.”

Since it was first sold, various sections of the Pentridge site have changed hands a number of times, with a number of different stages of demolition. Mann says that these days soaring blocks of flats are in the works, and much of the prison’s history – especially the years since 1900 – is being papered over.

“Prison is the place where the human experience is distilled down to its essence,” he says, adding that exploring Pentridge and listening to the stories of despair and sheer wretchedness had weighed heavily on him. Nevertheless, he enjoyed the old-fashioned gumshoe journalist work of tracking down potential interview subjects and inviting them to tell their stories. In one case, he travelled to Kuala Lumpur to find out what had happened to a former inmate. In another, he combed through old phone books, visited possible street addresses, and searched social media sites for relatives.

Many of the people he contacted refused, and the only woman prisoner interviewed for the book insisted on anonymity.

When Mann had made the connection, he took these interview subjects back to Pentridge for photographs. He remembers Noel Tovey, now a recognised figure in the arts world as the first Aboriginal ballet dancer, and awarded with an AM, walking back into the prison where he was incarcerated in 1951 for the “abominable” act of buggery, and Brian Morley, who as a journalist saw Ronald Ryan hanged, going back to the scene of state-sanctioned homicide that haunted him for so many decades.

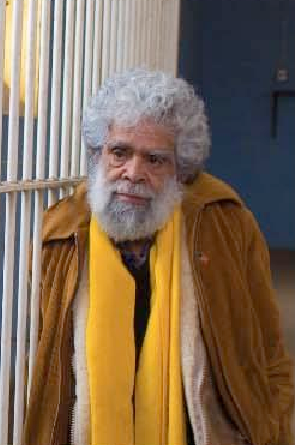

Ray Mooney outside B Division: his experiences there resulted in plays and books. Picture: Rupert Mann.

“To see Noel returning to cell for first time in almost 70 years, the cell where he tried to commit suicide, where his ancestors told him he would find a better life, to see him walk into that cell again and face that past, and to see Brian walk up to those gallows that horrified him and haunted him for almost his entire life: it was the antithesis of what the developers were doing, which was burying that history in order to make it palatable,” he says. “Noel and Brian were looking at it dead on”.

In recent times, Mexican-themed cocktail parties and fashion shows have been held at the blood-soaked site, and a two-hour ghost tour is on offer for $48 per visitor. At the same time, Mann says, a 19-storey block of apartments is planned for construction inside a small prison yard, surrounded by the massive blue-stone walls, with a watchtower at one corner.

Still, he adds, the current developers doing a better job at acknowledging the dark history of Pentridge than some of their predecessors, although many of the buildings associated with more recent memories of the site have already been demolished.

Although he understands something had to be done with Pentridge, simply because prime real estate in the middle of Melbourne could not simply be left to rot, he would have preferred a little more of the site’s tormented history to be preserved. “There’s a middle ground that could have been achieved”, he says. “Certain sections could have been left undeveloped, with more intensive development in other areas on the site”.

He finds the current mentality of pushing Pentridge as a delightful residential site a little difficult to understand, and likens it to Alcatraz being marketed as a convenient site for modern living.

“It would have been wonderful to have kept some areas of Pentridge, even just a couple of cells, with the original graffiti on the walls”, he says. “It was really a question for a heritage specialist, but unfortunately Heritage Victoria couldn’t force the developers to do it, and the National Trust and the Moreland Council, which opposed a lot of the development, didn’t have strong voice”.

This original graffiti, some of which is pictured on the inside front and back covers of Mann’s book, and has now been either demolished or painted over, is sometimes lurid, often obscene and occasionally pornographic. Unsurprisingly, it is liberally larded with swear-words as, indeed, are some of the first person interviews.

Mann didn’t flinch from using the obscenities, and neither did his publisher, Scribe, although he says some of his interview subjects had second thoughts after reading their transcriptions. Each subject had the right of veto, and Mann sent them copies of the interviews after they were conducted, and again, just before publication.

“By the time the book got close to publication, it had been six years since the interviews had been conducted, and quite late in the piece I decided that I needed to give all the interviewees the opportunity to look at it again”, he said, pointing out that some of the subjects, such as the respected Aboriginal actor Jack Charles, had become much more public figures, and it was only fair to offer them a second review.

“Most didn’t have changes, but some did,” Mann says, “and it pushed the book right to the line, that process”.

The singer Paul Kelly is another interview subject – he performed at Pentridge in 1985, and Peter Norden, a former chaplain at the prison, provides Mann with a reflective account of his time there. Pat Merlo, a former prison warden, was deeply upset by the suicide of a woman prisoner, and Franciscan Sister Clare McShee, who before she died in 2014 spent a long time counselling sex offenders locked up in the prison, remembered them with compassion.

Naturally, writing and compiling the book has prompted Mann to think deeply about the world of prisons and prison reform.

“Creative people, and people who see the world a bit differently, can naturally come up against the law”, he says, “because the law is rigid”. That rigidity has caused a lot of pain, he adds, and often almost unendurable suffering, but it also inspired a number of people to write, to act, and maybe to dance.

“There’s someone like Noel Tovey who’s written about his experiences in Pentridge in two autobiographies, and Ray Mooney, whose experiences in H Division (in Pentridge) resulted in plays and several books,” Mann says.

“Gregory David Roberts wrote ‘Shantaram’ in Pentridge, twice, because the prison officers found what he’d written on toilet paper and destroyed the book. And then he wrote it again from memory”. Before writing ‘Shantaram’, Roberts escaped from Pentridge in 1980 and fled to India where he lived for ten years. But he was later caught and sent back to Pentridge, where had to wait out another six years (including two in solitary). He claims prison guards twice destroyed his ‘Shantaram’ manuscript.

Law-breakers, like Roberts, and like some of those Mann interviewed, have often been physically or psychologically wounded by their peers, their parents or simply by the world, and locking them up does almost nothing to rehabilitate them and often only serves to entrench their anger and fear. He has found that the severity of the prison regime serves to hone humanity down to the bone, leaving only the primal emotions.

“Prison is a place where the human experience is distilled down to its essence,” Mann explains, mulling over his years of investigating, thinking and talking about Pentridge. “We believe prison is separate from the outside world, but in a way it’s more real than the real world,” he says. “People’s behaviour in prison reveals so much about the human condition, the resilience and fragility of the human spirit”.

Pentridge – Voices from the Other Side

Text and photographs by Rupert Mann

Published by Scribe

More information about Rupert Mann’s book can be found at www.pentridgeprison.org

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/pentridge-voices-from-the-other-side-preserves-prison-history/news-story/642c3eea0447face59163a8e56a4670c