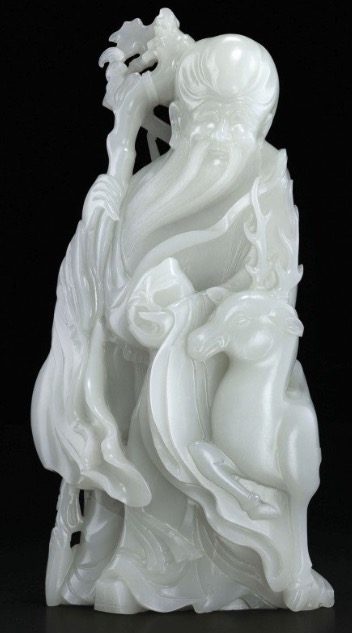

Qing dynasty treasures, including a carved white jade figure of the star god of longevity, Shulao, are scheduled for auction in Hong Kong on November 30 in a sale titled Imperial Glories from the Springfield Museums Collection.

The decision by Springfield Museums in Massachusetts to sell the 12 important China pieces, worth millions, follows recent government-commissioned reports in the Netherlands and France recommending the restitution of “war booty”, plundered during conflict, as well as pieces acquired for museums by colonial-era collectors who scooped up hundreds of thousands of items of art and historic interest from Europe’s colonial possessions.

A carved white jade figure of the star god of longevity, Shulao, said to be worth as much as HK$7 million.

Museums across Europe and the US are considering their options, and assessing which pieces should be returned to their countries of origin as the worldwide tide of sentiment regarding museums’ rights and responsibilities changes. National governments in Asia and Africa have asked for the return of items of important heritage for decades, and activists have become increasingly strident.

The Springfield Museums China pieces were “acquired” by US entrepreneur and collector George Walter Vincent Smith who died in 1923. The jade figure alone is estimated to be worth between HK$ 5 and 7 million.

The Springfield institution is shifting its collections’ emphasis. “Proceeds realised from the sale will be used for the care of collections and to advance the Museums’ commitment to equity, diversity and access through further art acquisitions by women artists, artists of colour and under-represented artists,” a publicity handout reads.

The global auction house Christies plans to put the Springfield pieces under the hammer after they have toured Beijing, Shanghai, Taipei and Hong Kong. Despite repeated attempts over a number of weeks to discuss the issue with a Christies’ representative, the response so far has been limited to a museum press release.

Christies was caught in controversy in 2009 when it planned to auction the bronze heads of a rabbit and a rat, two of 12 animal heads representing the Chinese zodiac originally taken by Anglo-French troops from Beijing’s Old Summer Palace in1860 during the Second Opium War.

Beijing pressed the auction house to withdraw the pieces, originally owned by French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent, saying the heads had been looted by “invaders”. The auction proceeded as planned, but the heads were eventually returned to China in 2013 by a French entrepreneur.

Pressure has since built on museums to re-evaluate the history and provenance of their collections. Sentiment spilling over from the Black Lives Matter movement in the US has fed into the volatile mix.

African activists have forcibly taken pieces from museums in Europe and posted footage of their “re-possessions” on social media; facing subsequent arrest and conviction. Earlier this year Congolese activist Mwazulu Diyabanza made a speech about cultural theft in a Paris museum then forcibly wrenched a funerary post from its display, guards stopped him as he left. He repeated his efforts in Marseilles the following month and then went the Netherlands to make his point.

In August, the British Museum, now temporarily closed due the Covid-19 pandemic, moved the bust of founder Hans Sloane from a prominent position to a glass case, with an explanation that his wealth had come from slave-holdings.

Long-known for its unwillingness to consider returns, the museum has introduced an online “collecting and empire” trail, explaining the provenance of various items, and before the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic, it quietly permitted “Stolen Goods” tours of the museum collections. Most recently the museum, which has resisted returning 950 so-called Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, has announced it will assist Nigeria to create a new museum and search for more archeological treasures

Dr John Carroll, a historian with the University of Hong Kong, says the reparations and restitution debate is “supremely complicated”, and one he expects to deepen with time, so it’s likely subjects on the rights and wrongs of reparations will be included in the university’s museums courses from now on.

“There should be legitimate dialogue,” he adds, pointing out the notion of restitution has been lumbered with emotional and political baggage. Conservatives, he says, often refuse to consider restitution at all, especially in the case of so-called legitimate purchases in bygone days, whereas liberals can automatically brand all museum acquisitions as theft.

“A lot of the museums today don’t even tell you the context of the exhibit,” he says. “There should at least be more explanation of how the thing got into the museum in the first place.

Detail of a metal and enamel vase to be auctioned by Christies, worth as much as an estimated HK$5 million.

France reignited this sector-wide museum collections rethink in 2018 when President Emmanuel Macron commissioned a report from two academics, asking them to come up with proposals for the return of artefacts of African national heritage.

The academics, Bénédicte Savoy from France and Felwine Sarr from Senegal, recommended that artefacts taken without consent should be permanently returned to their countries of origin, if the country of origin asked for them. The academics found that as much as 95 per cent of Africa’s cultural heritage is held by major museums outside Africa, and France alone has at least 90,000 artefacts from sub-Saharan Africa in its national collections.

In the Netherlands, in October, a far-reaching government-commissioned report by lawyer and human rights activist Lilian Goncalves-Ho Kang You and her committee, recommended the restitution of thousands of pieces of art and artefacts looted from Dutch colonies including Indonesia, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, South Africa and Surinam.

Major Dutch museums have backed the report’s idea for a wholesale “recognition and rectification of these injustices”, emphasising a return where “involuntary loss” is confirmed.

Jos van Buerden, a Dutch scholar who wrote a book on restitution, Treasures in Trusted Hands, published by Sidestone, has been an active researcher in the field for years, and he says some of the bigger Dutch museums are getting ready for the return of artefacts and art.

“We might say this advice to the Dutch government is a tipping point; there seems to be general atmosphere that we really have to face this issue,” he says, adding there was a widespread recognition that many items in the collections of European museums had been taken by force, and even pieces that were purchased rather than forcibly taken could be returned.

“The Dutch advice admits injustice,” van Buerden says. “It also has a rather broad definition of objects that can be returned to countries of separation. If objects are of more importance for the country of origin than for the Netherlands, then even if they were voluntarily separated there is an option for them to be returned.”

It won’t be easy. One Dutch curator has been quoted pondering the nature of the returns. The famed Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, for instance, has a diamond that was once owned by the Sultan of Banjarmasin in present-day Kalimantan in Indonesia.

The museum’s online caption states: “The diamond is war booty …. In 1859 Dutch troops violently seized control of Banjarmasin and abolished the sultanate. The rough diamond was sent to the Netherlands where it was cut into a rectangle of 36 carats.”

So, the curator wondered, should the diamond be returned to Indonesia’s national government in Jakarta, or to the provincial authorities in Kalimantan, or to the Sultan’s heirs?

Provenance, and determining rightful recipients, will always be difficult, van Buerden says. “It’s one of the most difficult discussions in the whole restitution issue, in my view,” he adds. The model of the restitution committee for Nazi-looted art is an example of how it can start, he says, adding that despite the seemingly good intentions of the Dutch and French reports and an increasing feeling that war booty, at the very least, should be returned, very little has been done.

“Germany has returned two objects to Namibia,” he says. “Macron has offered 26 to Republic of Benin in West Africa. The Netherlands returned one kris, or dagger, to Indonesia.”

Apologists, he points out, use the context argument: saying museums provide a place for items of a similar nature from around the world to be seen in context, as they relate to one another and to world history.

“Yes, they want to keep the objects they have,” he says. “They consider themselves better guardians.”

Most of these artefacts, though, were not made for museum display, but for temples and ceremonies, he points out. European conquerors and colonialists had a magpie mentality, collecting whatever took their eye.

“It was the greed culture of European countries during the colonial era,” van Buerden says. “They took as much as they could.”

https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/arts-culture/article/3110637/western-museums-pressed-return-stolen-treasures-asia-and