Landlocked and mountainous, with an extreme climate veering between the numbing cold of snow and ice and blistering desert heat, the insular nation of Afghanistan has never been successfully occupied. The British were routed, twice; the Russians were given the push after years of bloody insurrection. And now the post-September 11 alliance, dominated by the US and including Australia, France, Britain, Canada, Germany, The Netherlands and many other nations, has largely withdrawn from the severe, primitive and often brutal country, allowing it to slide back into its age-old ways.

After Australian forces pulled out of Oruzgan province in 2013, the Taliban rapidly regained the strongholds of Chora, Shahid-e-Hasas and Khas Oruzgan. Across Afghanistan, the numbers of black-clad zealots have now at least trebled since the beginning of the conflict, according to US information. They have slowly but surely pushed their way back into many other areas of Afghanistan, retaking control of as much as 40 per cent of the nation.

For now, at least, illicit opium poppy will continue to be grown (production reached an all-time high in 2014), heroin will be made and sold, women will wear burkas and many girls will never go to school.

For now, at least, illicit opium poppy will continue to be grown (production reached an all-time high in 2014), heroin will be made and sold, women will wear burkas and many girls will never go to school.

Yet again the blood-soaked Afghanistan lesson has been learned, this time at a cost of thousands of lives on both sides, and many billions of dollars. Overwhelming force and sophisticated weaponry cannot defeat an elusive and cunning underground enemy, one who melts into the background and uses guerilla tactics with cunning and guile. The alliance might have deployed the feared drones known as Predator UAVs, as well as Hellfire missiles, Spectre gunships and machine guns, but the Taliban could assemble deadly underground bombs and suicide vests for a handful of dollars.

Even Australia’s Javelin missiles, worth $100,000 a pop, and relentless Special Forces soldiers failed to turn the tide permanently against Taliban forces fighting on their own ground, unhampered by rules of engagement or concerns about so-called collateral damage.

Perhaps most importantly, the hearts and minds of Afghans cannot easily be won by aggressive foreign troops, most of whom do not speak the local languages or understand the customs and religion of the land. At the same time, savage reprisals from the Taliban lay in store for alliance sympathisers.

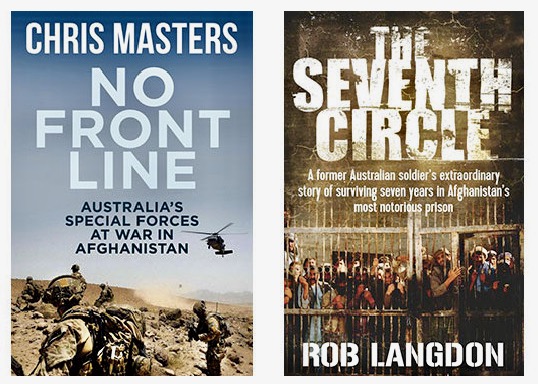

Award-winning journalist Chris Masters’s No Front Line is a comprehensive history of the war Australia’s Special Forces waged for 12 long years in Afghanistan. Given unusual access to the usually secretive elite soldiers (many of whom he identifies only by their first names), he has put together a solidly researched book capturing a part of Australia’s longest war.

He details the extraordinary bravery of many individuals: the soldier who wrapped a chain around his head to deflect bullets; another who ran into gunfire to rescue a fallen comrade; another who managed to fix a broken vehicle in searing heat and in the middle of a gunfight.

Often the first sign these soldiers had of a looming hail of bullets, or a bitter and brutal ambush, was the sight of Afghan women and children hurrying away. Keyed up, adrenalin rushing, nerves twitching, these soldiers lived on the edge, often for weeks and months at a time, so it’s little wonder that nuance and civil negotiation could be lost in the rush.

No Front Line is by no means a hagiography, and admirable acts of valour are set alongside mistakes, some careless actions and, most importantly, the overall failure to better the lives of the Afghans the troops were attempting to protect. As Masters notes, the history of Australia’s war in Afghanistan has been tainted by allegations of soldiers’ brutality, of untoward aggression, the desecration of corpses and unwarranted shootings.

Closer to home, the stress of war with an often invisible enemy, one who can blow up your vehicle on a routine patrol or insert a murderous traitor into your midst, has taken its toll on Australian soldiers. There has been concern about heavy drinking, punch-ups, drug-taking, post-traumatic stress and, tragically, suicide.

Over 12 years, about 300 Special Forces troops rotated into Afghanistan, recovered and returned. Roughly 3500 TIC (troops in contact with the enemy) incidents were counted, 3000 of them by Special Forces. Fewer than 1000 Australian soldiers killed between 4000 and 5000 enemy fighters, Masters notes, and most deaths were connected to the Special Forces. By the Australian Defence Force’s estimation, not since World War I have Australians engaged in such intense and sustained conflict, which left 42 Australian soldiers dead during operations in Afghanistan, 21 of them Special Forces.

The soldiers’ courage and skill is unquestioned. Victoria Crosses were won and medals of gallantry awarded. Yet it seems no amount of sheer bravery and professional expertise can decisively win that kind of asymmetical war.

The conflict was further complicated by neighbouring Pakistan, which provided a safe haven for Taliban leaders. Opium poppies provided the Taliban with a ready source of income to fund their war. Among Australians, moral fatigue finally began to set in.

Masters comes to the conclusion that instead of soldiers ready to fight and kill, the Afghanistan campaign really needed a civilian aid task force, with language, cultural and negotiation skills, staffed with experts prepared to face danger and live rough. Sadly, this sort of force would have been nigh on impossible to assemble and deploy. Now, to stem the bloodshed and regain some measure of stability, some accommodation has to be reached with the Taliban, and this has to be the business of the government of Afghanistan.

Rob Langdon’s view of Afghanistan is far more focused than Masters’s comprehensive understanding, and mostly from the inside of a barebones jail. In his book, The Seventh Circle, Langdon explains how he shot his Afghan colleague dead at point-blank range, blew the body up with explosives, and tried to flee the country.

Wrong-headed and negligent? Probably. Homicidal? Possibly. For his part, the one-time Australian soldier says he was sleep-deprived and tense at the fatal moment, and the killing was simple self-defence.

Working for a “dodgy” private security contractor in the conflict-racked nation, Langdon was stuck with a convoy of trucks in a hazardous location outside Kabul. His colleague Karim was refusing to get the trucks moving and, Langdon thought, he was possibly in cahoots with Taliban insurgents.

Langdon adds that when he confronted Karim about the delay, Karim pointed a pistol at his face. So Langdon jerked up his assault rifle and shot Karim dead. To make matters worse, Langdon says he then felt compelled to blow up Karim’s car because he found the boot was full of what he assumed were contraband narcotics, which he knew could land him in a world of trouble (still, why not simply hurl the drugs into the largely empty Afghan desert? Who knows?). Then, Langdon explains, Karim’s corpse was somehow left or forgotten in the car’s boot by Langdon’s Afghan assistants. So when he tossed a grenade into the car to destroy the drugs and other evidence, Karim’s body was blown up as well.

A corpse would seem to be a difficult detail to overlook, yet Langdon says that somehow it was. He knew it would be hard to explain a blown-up body, as well as a killing and a car explosion. Running, he got as far as Kabul airport before he says he was caught by Afghan police, repeatedly beaten and kicked, and locked up in prison.

With no witnesses to Karim’s death, Langdon’s case would have led to a difficult trial even in an Australian court. But Afghan justice, as Langdon points out, is something else. In remarkably short order, he was sentenced to death by a judge, though his lawyer wasn’t present and no interpreter was provided.

Compassion and civility don’t last long in the badlands of Afghanistan. Langdon had killed before, he says in his book, and he wasn’t particularly remorseful about killing Karim, at one point calling his death “a stupid incident”.

In his memoir of his long years in an Afghan prison, the title presumably a nod to Dante’s Inferno and its nine circles of hell, Langdon blames any number of people for his predicament and long incarceration, saying he was sold out and betrayed: by his crooked boss; by a colleague; by a fellow-prisoner; by an ex-flatmate and business partner; and by an Australian reporter in Kabul.

Afghanistan has been a byword for lawlessness for years. Of course it’s hard to stay calm and make rational decisions, with bullets and grenades flying about and potential turncoats riding along in the convoy, and easy for tensions to escalate into violence. Still, Langdon’s tale raises a number of uncomfortable questions about how private security contractors operate in war zones such as Afghanistan and Iraq, about their rights and their responsibilities, and where the line of culpability is drawn.

Langdon claims the firm he was working for, Four Horsemen, was not only ignoring obvious corruption, but some staff were participating in bribing Afghan officials and smuggling contraband in the convoys. Carrying US mail and materiel, and often travelling under a mantle of US protection, the convoys were ideal cover for moving illicit goods.

In the end, Langdon spent seven years in an Afghan prison before he was released last year. Written with the assistance of Australian journalist and author Malcolm Knox, his memoir is a catalogue of the difficulties and mortifications of life in a grisly prison somewhere outside Kabul. Horrifying executions, assaults, rapes, bullying: Langdon witnessed and endured a great deal.

He notes the solitude, the filth, the danger, the uncertainty, the violence and the sheer boredom of life in Pul-e-Charkhi, a prison he calls “the worst place on earth”.

He had various means of communication, including a smartphone, stashed in secret places. In the beginning, before travel became too dangerous, embassy staff visited regularly and brought food. Friends brought more food. At various and sometimes overlapping stages, Langdon had a cell to himself, a television, a stove, a kettle and a pet cat.

Finally, his death sentence was lifted (only after hefty compensation was paid to the family of the dead man) and eventually he was freed. The Seventh Circle is one man’s raw vision of Afghanistan, that comfortless and austere nation that has claimed so many lives over the centuries, and inflicted so much pain.

No Front Line: Australia’s Special Forces at War in Afghanistan

By Chris Masters

Allen & Unwin, 608pp, $32.99

The Seventh Circle

By Rob Langdon

Allen & Unwin, 293pp, $32.99

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/no-front-line-australias-special-forces-in-afghanistan-seventh-circle/news-story/0115c8d918184c1035cd80c899ce979e